Shinjuku, Tokyo. The pulsing heart of modern Japan. Electric, overwhelming, Asian chaos. Total sensory overload. The only possible comparison for the visitor, still after all these years, is Blade Runner.

For the natives, Shinjuku Station is a transfer point, a place to jump a commuter train and hop on the bullet. Leave the six-story station/fortress at any one of sixty exits in any direction, and your money is immediately up for grabs: dig the curbside ramen, electronic emporiums, prostitutes from around the world, video game arcades, titanic department stores. Gorge on fast food, gourmet dining. Get wild with bootleg-CD box sets. Snap up those movie tickets.

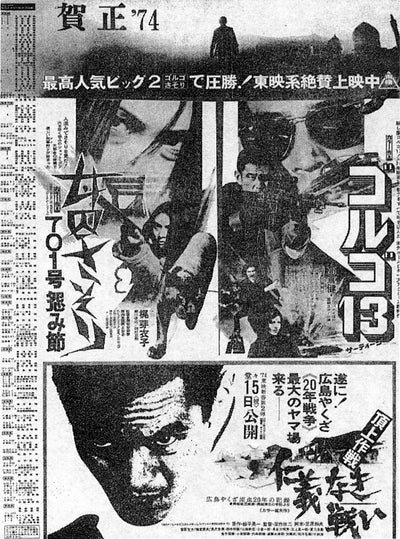

Immense billboards next to East Exit advertise what’s playing at the Toei- and Toho-owned theaters in nearby Kabuki-cho. In late summer 2000, massive campaigns were in effect for Setsuro Wakamatsu’s Whiteout and the Wayans brothers’ Scary Movie.

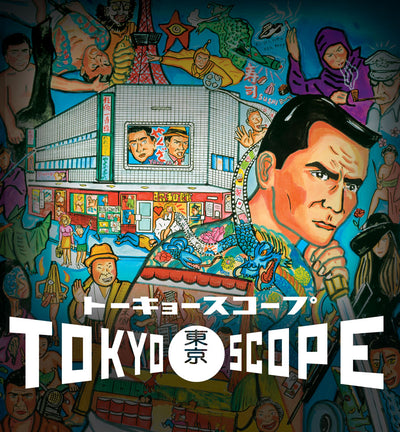

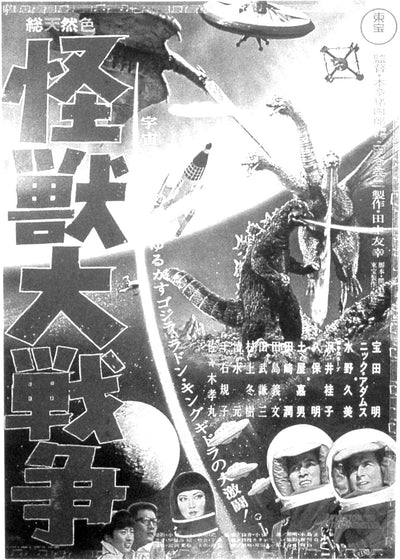

Head south. Stay off the main thoroughfares. Get lost down the numerous side streets and alleys. Explore. Pass the cell-phone kiosks, the sex shops, and pachinko parlors. A grid of ancient-looking movie posters will strategically appear out of the ether: snarling faces framed by guns and knives. Yazuka. Gamblers. Tumbling dice and hanafuda cards.

This is how the Shinjuku Showakan announces itself, in images frozen in time from Japan’s Showa era (1925-1989).

Don’t sneeze at the ¥1300 admission fee. You’ve saved a few, compared to the ¥1800 admission for a first-run flick, and can use it on the vending machine in the lobby. Pay the nice old lady inside the box-office window. She’ll tear your stub in half.

Walk inside. Look around. Try not to sniff around too much. Curious smells might give you a bad first impression. Adjust the eyes. Some two hundred seats make up the main floor, with additional seating located in a spacious balcony. There’s maybe only forty to sixty or so people in there along with you. Most of them are middle-aged men.

The Japanese word for them is oyaji. And in a culture that worships youth and style, they are probably the most unfashionable people in the country. First and foremost, the Showakan is their place. A hardcore contingent, the Showakan Army, lines up every day before the doors open at noon. They come for all kinds of reasons. To get off of the street. To crash on the cheap. Others come because they have no stomach for Hollywood film, televised entertainment consisting of pop stars eating exotic foods, or trendy dramas about everyday life. The Showakan’s films used to represent the mainstream of Japanese pop cinema. Now these old movies are as alternative as it gets. The Showakan is also a clubhouse for the local yakuza. And with movies like Nihon no don (The Don of Japan) and Soshiki boryoku (Organized Violence) constantly playing, how could it not be?

Perhaps because of the Showakan’s rough-hewn clientele, a bad reputation hovers around the place. Mention it to people out of the inner circle and they’ll warn you about the place as if it were a dragon’s lair minus any treasure. Once inside though, the joint turns out to be down home and nearly benign. By promixity alone, simply walking through the door makes you an honorary oyaji or temporary yakuza.

As if to show there is nothing to be anxious about, some patrons are asleep, peacefully oblivious to whatever might be playing on the screen. Others are prone to distraction, endlessly rummaging through plastic bags, muttering to themselves or at the screen (especially when guns or breasts appear). Still others watch intently. They’ve been inside the theater all day. From the glazed looks of them, perhaps all their lives.

The Showakan’s doors first opened in 1932, when the theater specialized in foreign films (meaning American and European fare), then during World War II it was burnt to the ground, like much of the surrounding area, by Allied fire bombings.

The Showakan rose from the ashes in 1951. Once rebuilt, it played what the major Japanese studios offered and what the public wanted to see. Mostly this meant sword films or yakuza films with period flavor. There was one major patriotic stipulation: the films would have to be Japanese. If the Showakan was going to cultivate a loyal audience, then it had to draw the line somewhere.

In the sixties, as the all-pervasive popularity of television began to shut down theaters, and domestic studios sold their property to cash in on the growing value of real estate, the Showakan managed to hang on. You can thank the yakuza for that mostly, even though they sometimes demanded free admission from the hapless staff. During turf wars, fights could break out between rowdy patrons. Toei shot scenes for movies inside. The programming switched to triple bills daily, and time marched on, at least outside the increasingly hermetically sealed Showakan.

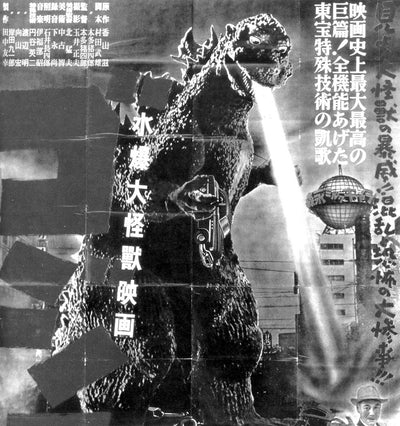

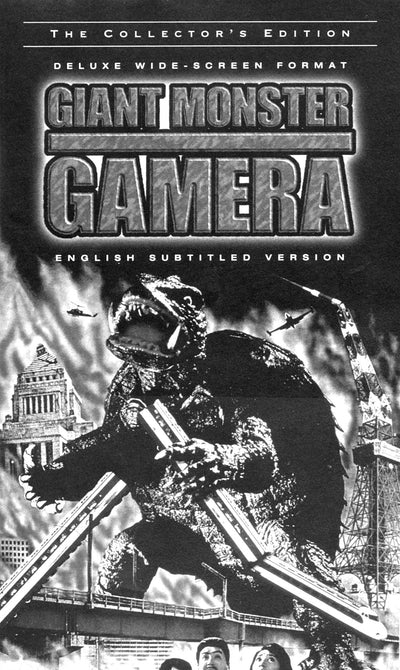

Then as now, two genres utterly dominate the programming: yakuza films and horror movies. Sonny Chiba is a big draw here. So is anything directed by Nobuo Nakagawa. Far and away the most popular fare is culled from Kinji Fukasaku’s seventies-era Jingi naki tatakai (Fight without Honor and Humanity) series.

The management is constantly struggling to obtain raw materials, but film prints, some of which have been in circulation for upwards of thirty years, are not always in the best of shape. The same goes for what little advertising materials the studios can be bothered to cough up. When original posters and film stills are not available, illustrator and Showakan schedule-maker Happy Ujihashi goes to work and paints smashing new interpretations all his own. He also creates a monthly Showakan News flyer that’s distributed throughout the neighborhood.

So the place might be a little beat-up in places. (Whoa! Watch out for that bathroom.) There’s still much to be proud of. Sound and projection are first-rate. So is the programming. Living history in light and shadow.

The Showakan management has made recent attempts to turn the oyaji onto new stuff from time to time. In 2000, recent films such as Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Serpent’s Path and Sabu’s Dangan Runner (aka Non-Stop) were screened and well received. But the crowd is picky. Takashi Miike’s Dead or Alive seemed like a sure thing, until the English title confused the patrons. Thinking that Kinji Fukasaku could always be counted on, Battle Royale was booked. But it seemed that the old timers didn’t want to watch a movie about high school kids. Especially one with an English title.

Give it another thirty years or so. The next generation of oyaji will probably need a place deep in Tokyo to call home, too. And the Showakan will be there to mop up when they do.