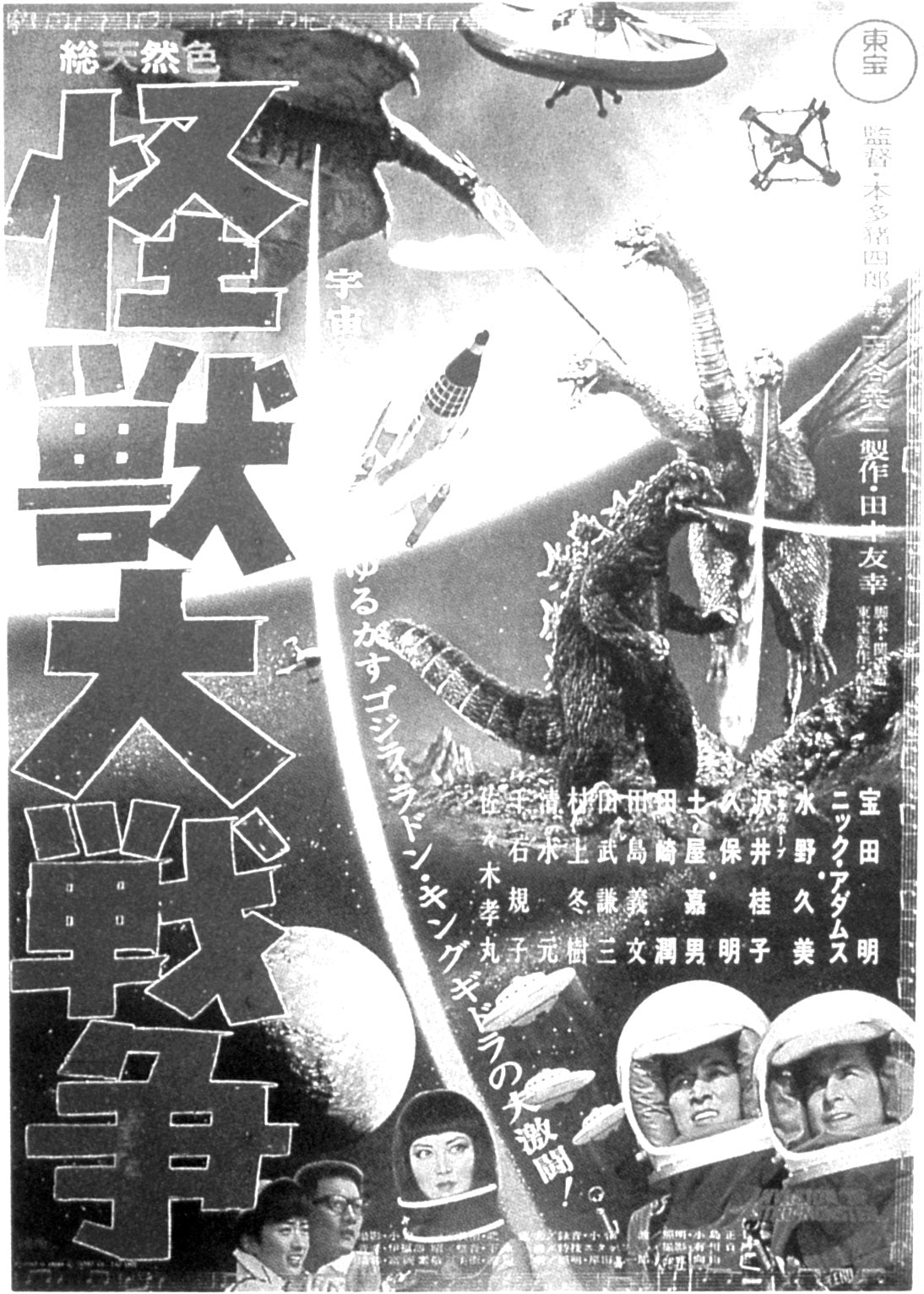

Godzilla vs. Monster Zero

Kaiju dai senso (Great War of the Monsters)

1965, Toho

Director Ishiro Honda

Cast Nick Adams, Kumi Mizuno, Yoshio Tsuchiya, Akira Takarata

The War and Peace of the Godzilla series, a tale of star-crossed love and interstellar conflict, fraught with radio waves, light rays, personal-guard alarms, and no less than three giant monsters—Godzilla, Rodan, King Ghidorah—running amok across two planets.

A role call of stock scientists, inventors, army men, and alien invaders suggests at first that Godzilla vs. Monster Zero might be little different from numerous other Japanese monster films. Even the cosmos had been breached before in Honda’s Chikyu boeigun (aka The Mysterians, 1957) and Uchu dai senso (Battle in Outer Space, 1959), both gorgeous pulp illustrations come to life.

And yet Monster Zero contains perhaps the most passionate and emotional moments to be found in the entire Godzilla oeuvre. It detonates from the inside with improper conduct.

Rhona Barrett-like reports from the field have suggested that married-with-children American star Nick Adams (who plays “Astronaut Glen” with all-American full-throttle ferocity) and costar Kumi Mizuno, Toho’s resident sex bomb (in the part of “fetching alien spy from Planet X”), were most likely getting it on.

With the fallout from this troubled affair spilling over into the performances, Monster Zero is less a simple Godzilla movie and more of a prism reflecting back the dangerous liaisons of Nick and Kumi, human and alien, East and West. Few who see Nick grabbing Kumi, clad in black and gray alien fetish gear, by the shoulders and shouting something about “happiness in this world” having less worth than “a hill of beans” can forget it. Think that it’s over the top? This is the top.

It’s also a first-rate Godzilla film. In fact, it’s the final hurrah for the classic core Toho staff before turning their monster over to others for inevitable downsizing and diminishing returns. Everything about Monster Zero is tight and crisp, designed with a snappy sense of mid-sixties style.

A sequel would have been great. Nick, who would be found dead under mysterious circumstances in 1970, surely would have gone on to become the ambassador of a defeated planet where every woman looked like his late fiancée. And perhaps then the monster movies that followed would have had as much human soul as they would men-in-suits.

[author bio="Follow the author and the book here!" image="author-pat2.jpg" facebook="http://facebook.com/Otakuversezero" twitter="http://twitter.com/patrick_macias" website="https://www.amazon.com/TokyoScope-Japanese-Cult-Film-Companion/dp/1569316813"]

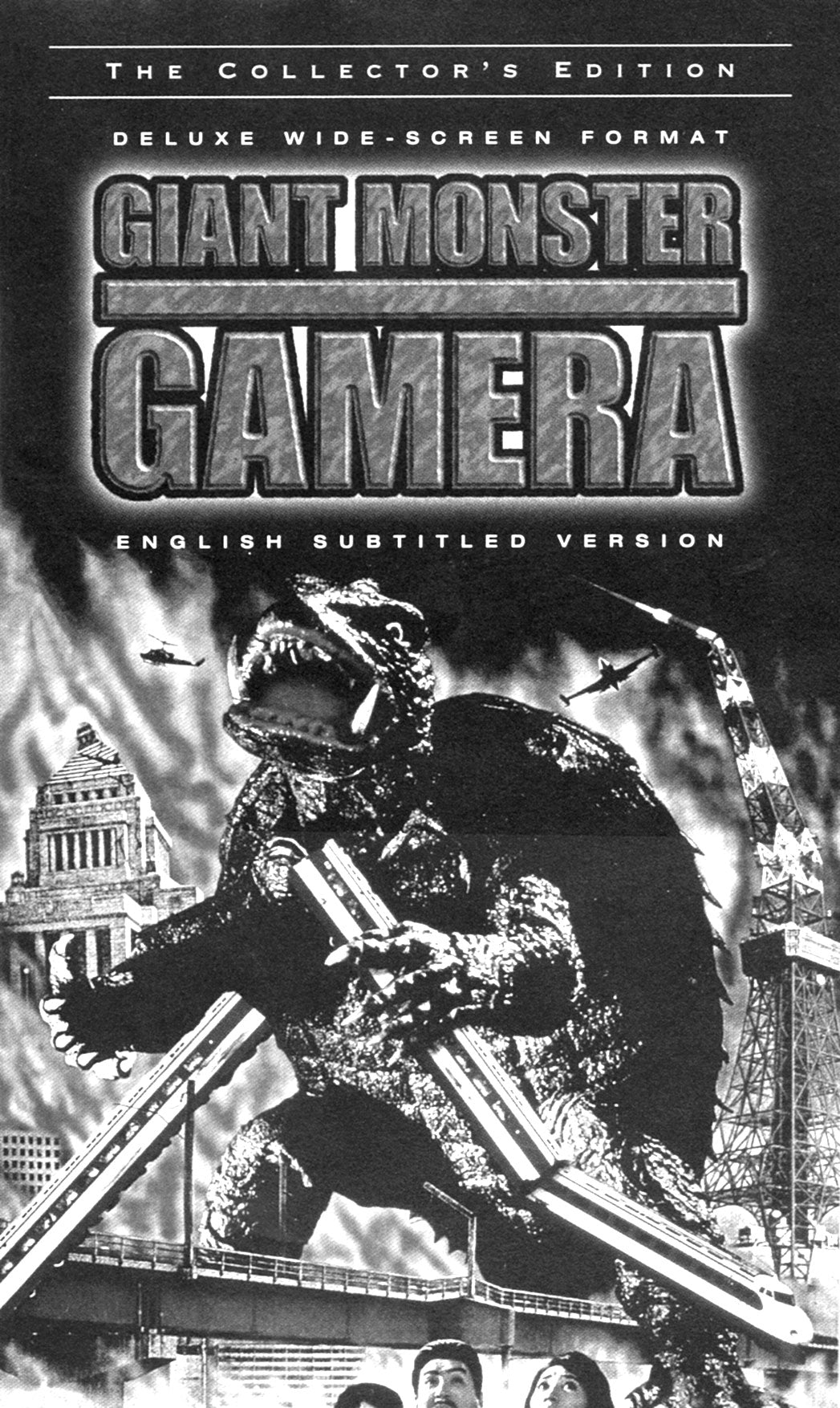

Giant Monster Gamera

Dai kaiju Gamera, aka Gamera the Invincible

1965, Daiei

Director Noriaki Yuasa

Cast Eiji Funankoshi, Junichiro Yamashita, Michiko Sugata, Harumi Kiritachi

Gamera, a giant flying jet-propelled turtle, sounds like an insane idea to base an entire movie series around. But it becomes almost pedestrian when you hear that the film Dai kaiju Gamera originally evolved from the ruins of a proposed swarm-of-giant-rats film, a project that was canceled when its real-life rodent stars—and indeed portions of Daiei’s studio—were besieged by a plague of fleas.

Stuck with an abundance of surplus miniature city, producer Masaichi Nagata (Rashomon) was struck by a vision of a flying turtle and decided to make a kaiju quickie with second-time director Noriaki Yuasa at the helm.

Whereas Godzilla took at least half an hour to get to his very first close-up, Gamera pops up, jack-in-the-box style, five minutes after the appearance of the opening Daiei logo. The grim shadow of the Cold War looms large at the beginning, but things wrap on an upbeat note as the world unites as one to combat Gamera.

Gamera also marks the introduction of what would soon emerge as a major theme of kaiju eiga: the alliance between children and monsters. The soul of the film is Toshio, a troubled, motherless kid obsessed with turtles. He is convinced that his AWOL terrapin pet has somehow become the giant, indestructible Gamera.

Even as the monster blows up power plants and burns Tokyo citizens to a crisp, Toshio is convinced that Gamera is a good guy and is merely misunderstood. Meanwhile, the adults just keep trying to find a way to get rid of the monster, which at one point kills thousands in Tokyo, all the while trying to break down Toshio’s imaginary world. But since Gamera functions more as psychological projection than as atom-age nightmare, simply shooting him into space won’t work for long. And it didn’t, as the successive increasingly childish Gamera films would prove.

At one point in the film, one of the adults asks, “When World War III breaks out, why bother with turtles?” Clearly, there’s a generation gap at work here. The grown-ups don’t know, but the little boys understand.

[author bio="Follow the author and the book here!" image="author-pat2.jpg" facebook="http://facebook.com/Otakuversezero" twitter="http://twitter.com/patrick_macias" website="https://www.amazon.com/TokyoScope-Japanese-Cult-Film-Companion/dp/1569316813"]

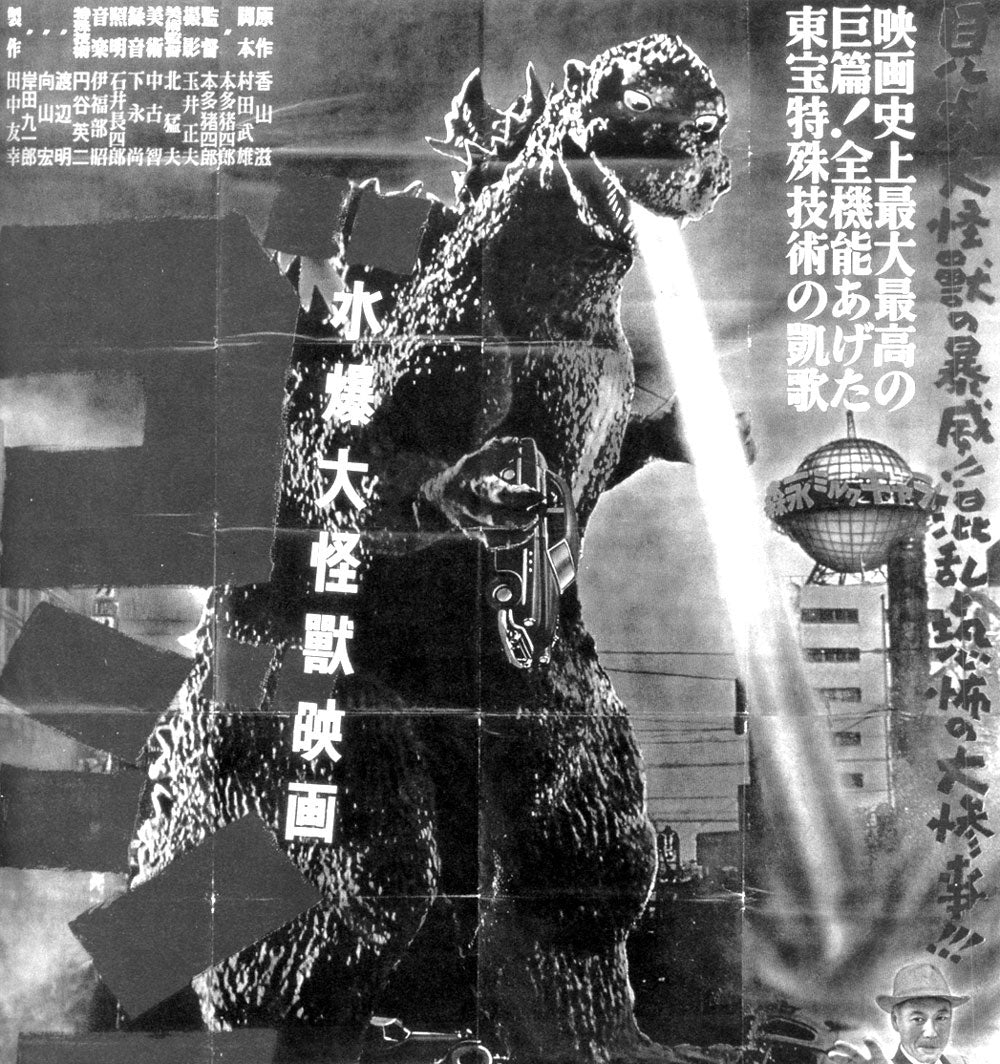

Godzilla

Gojira

1954, Toho

Director Ishiro Honda

Cast Takashi Shimura, Momoko Kochi, Akira Takarata, Akihiko Hirata

A mysterious force destroys a Japanese fishing boat at sea. The families of the missing demand answers. A subsequent investigation leads to terrible revelations.

The scenario plays like a nightmare headline, the ink only beginning to dry. A collision between a US Navy submarine and a Japanese fishing vessel? No, the opening chain of events from Gojira, the first Godzilla movie.

The unaltered 1954 Gojira is a film shown so seldom outside Japan one might think it suppressed. No wonder. Half a century on, Gojira, a conscious exploration of unconscious fears, still taps into national traumas and anxieties.

“Behind the fear of Gojira was the fear of the atomic bomb,” wrote director Ishiro Honda, in an essay. “We thought that if we were to shy away from it, even a little bit, the film would not be completely successful.”

Japanese audiences witnessed scenes which directly addressed the horror and banality of life in the then newly minted atom age. Much of this aspect is absent from the 1956 Americanized re-edit of the film, Godzilla, King of the Monsters, which instead opts for placing the reassuring face of Raymond Burr center-screen. It’s Perry Mason vs. Godzilla.

In the Japanese Gojira, a TV crew catches sight of a mutant dinosaur awakened by atomic testing and assures us that, “This is not a movie or a play.” The high-contrast black-and-white footage resembles a newsreel taken at ground zero.

Honda did his utmost to give his Gojira documentary strength; the point of view is informed by personal experience and real catastrophe. As the principal characters watch Tokyo Bay and much of the surrounding city burn down, the feeling is far away from popcorn entertainment. You can’t root for this monster or even vicariously enjoy the carnage it creates. The mood is somber and one of pure helplessness.

Gojira is the bomb. Gojira is the Great Kanto Earthquake. Gojira is the sound of thunder coming down from the mountain. Gojira is a multi-purpose symbol for destruction incarnate.

Fifty years on, Godzilla is a pop icon, but, in a new era of sunken fishing boats and mad science, the original Gojira still haunts the seas.

[author bio="Follow the author and the book here!" image="author-pat2.jpg" facebook="http://facebook.com/Otakuversezero" twitter="http://twitter.com/patrick_macias" website="https://www.amazon.com/TokyoScope-Japanese-Cult-Film-Companion/dp/1569316813"]

“KAIJU EIGA”— MONSTER MOVIES

Art attempts to create the impossible with limited means. Sometimes this gives birth to works of greatness. Sometimes it leads to giant monsters.

Is the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel the actual Glory of the Almighty made manifest? No, it is more like a really good celebrity impersonation.

And whatever you feel about movies such as Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster or War of the Gargantuas, Japanese monsters are part of this noble tradition.

In addition to wielding paint and brushes, the filmmakers and technicians behind Godzilla, Gamera, and their kith and kin must keep a very big palette at their disposal, one with rubber monster costumes, optical printers, miniature cities, and computers in order to create an illusion of reality.

“Film is a synthetic art form in every respect,” said the late Ishiro Honda, director of 1954’s Gojira (Godzilla) and one of the founding fathers of the tokusatsu, or special-effects film. “It is also a form of synthetic techniques. The filmmaker is an artist, but at the same time he must also be a scientific technician.”

Michelangelo, himself a multitasking sculptor, architect, painter, and poet, would have made great monster movies.

After studying 1933’s King Kong and 1953’s The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, and using special-effects skills gleaned from numerous domestically produced World War II propaganda films (such as 1942’s The War at Sea: From Hawaii to Malay), it was the Japanese who erected the dynasty of the kaiju eiga—the giant monster movie.

Even if you’ve never heard of Gappa the Triphibian Monster or Gamera the Invincible, everyone knows Godzilla. From Thailand to Germany (even though, okay, he’s been sold there on occasion under the name of “Frankenstein”), and all points in between, no other Japanese films are as widely seen or available. The Lizard King receives more recognition, and garners a bigger audience, than Akira Kurosawa.

Gomer Pyle was a Godzilla fan. But so is Martin Scorsese, who once asked to meet Ishiro Honda on the basis of the fondly remembered films he saw as a kid in a Brooklyn theater.

Kaiju eiga are the films of one’s childhood, screened at matinees and on Saturday morning TV. In Japan, entire tokusatsu films were cobbled together and edited down just to show at kiddie film festivals. Why not? Stepping on a city and spewing atomic heat death is the ultimate temper tantrum. To criticize these films as childish is redundant.

At the other extreme, some people take kaiju films as seriously as sacred texts. Academics concoct overreaching theories about them regarding the state apparatus of postwar Japan. Hollywood pisses away millions on a stale American Godzilla movie. Humorless fans threaten to kill each other over which Godzilla suit was best designed.

In truth, there was only one great explosion. All else has been aftermath, an illusion of life in the bomb shelter.

Toho Studios’ original Gojira (1954) was an anxiety-ridden film explicitly about the H-bomb, an unprecedented mix of monstrous fantasy and documentary reality, the juxtaposition of ticking Geiger counter and dazed child its single most disturbing image.

Follow-ups would handle the primal theme either too lightly (King Kong vs. Godzilla), too heavy-handedly (Godzilla 1985), or not at all. References to reality gave way to a flood of fantasy. But every now and then, synchronicity steps in and reminds us where it all began.

In Godzilla 2000 (actually a pretty poor excuse for a Godzilla film), the monster attacks a nuclear power plant in Tokai. It is exactly the same location where a critical nuclear fuel plant accident occurred on September 30, 1999. Heavy handed allegory? But the script to Godzilla 2000 was already well completed before the accident.

If the genre has long since reached its dead end and chosen to endlessly reenact the same rituals (the winking self-awareness of Gamera III admits as much), kaiju eiga will forever function as Trojan horse—as point of entry into the less traveled woods of Japanese film and worlds beyond. Those hooked on Godzilla at an early age may, by adulthood, know that Toho producer Tomoyuki Tanaka was not only behind numerous Godzilla films, but also Kurosawa’s The Bad Sleep Well.

Giant monster movies and the sublime are not as far apart as they seem. Kurosawa may have gotten the accolades, but the monsters got something more. A mythology, a religion, even.

In Godzilla we trust.

[author bio="Follow the author and the book here!" image="author-pat2.jpg" facebook="http://facebook.com/Otakuversezero" twitter="http://twitter.com/patrick_macias" website="https://www.amazon.com/TokyoScope-Japanese-Cult-Film-Companion/dp/1569316813"]

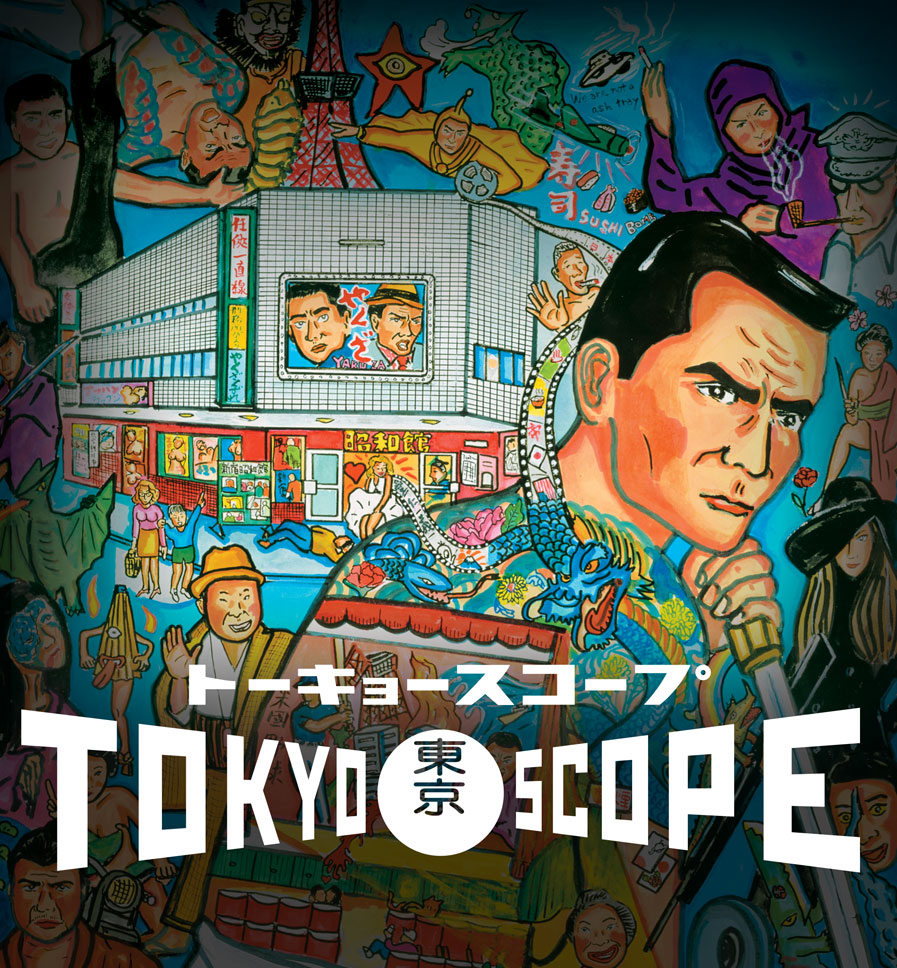

THE SHINJUKU SHOWAKAN

Shinjuku, Tokyo. The pulsing heart of modern Japan. Electric, overwhelming, Asian chaos. Total sensory overload. The only possible comparison for the visitor, still after all these years, is Blade Runner.

For the natives, Shinjuku Station is a transfer point, a place to jump a commuter train and hop on the bullet. Leave the six-story station/fortress at any one of sixty exits in any direction, and your money is immediately up for grabs: dig the curbside ramen, electronic emporiums, prostitutes from around the world, video game arcades, titanic department stores. Gorge on fast food, gourmet dining. Get wild with bootleg-CD box sets. Snap up those movie tickets.

Immense billboards next to East Exit advertise what’s playing at the Toei- and Toho-owned theaters in nearby Kabuki-cho. In late summer 2000, massive campaigns were in effect for Setsuro Wakamatsu’s Whiteout and the Wayans brothers’ Scary Movie.

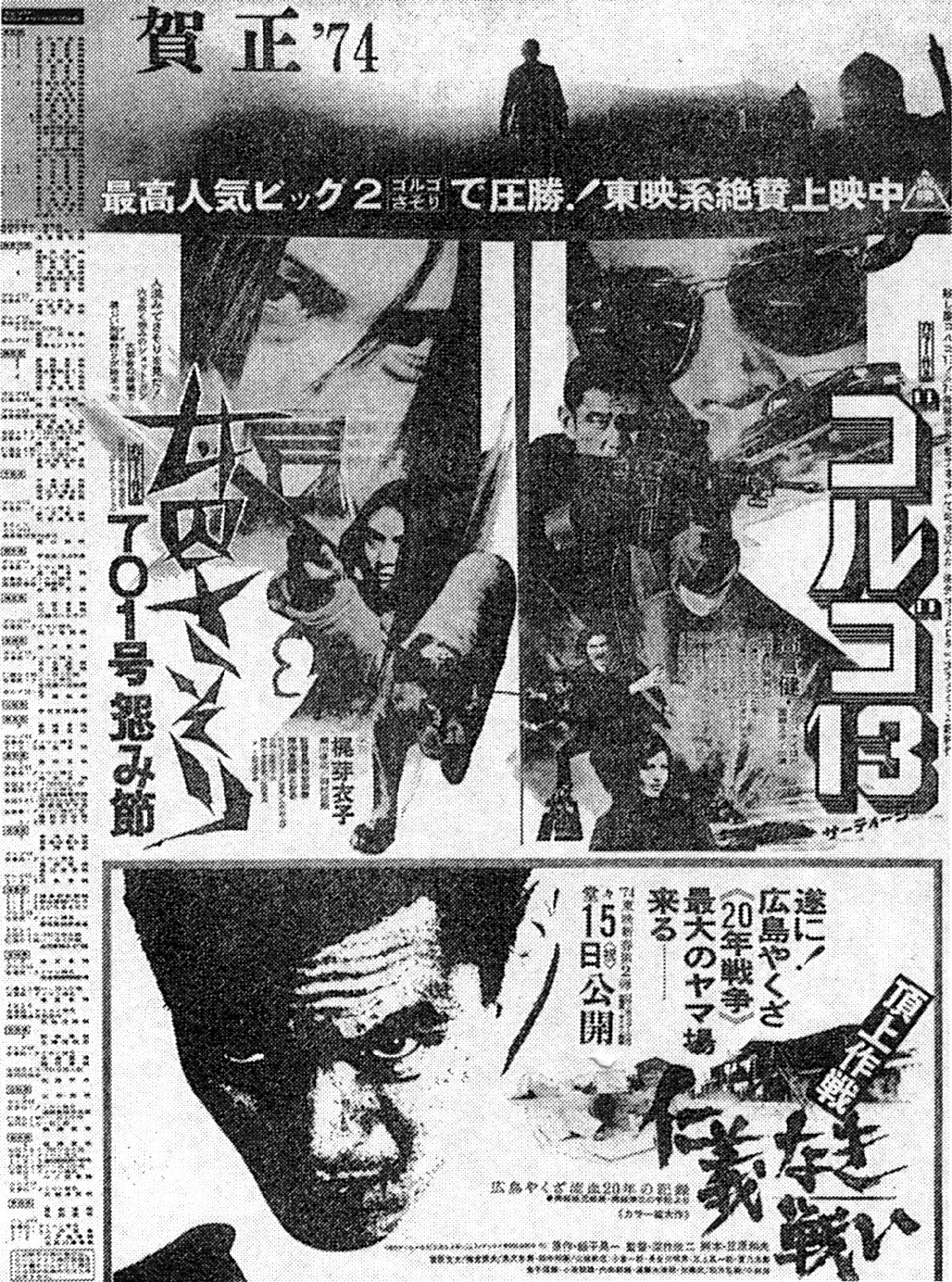

Head south. Stay off the main thoroughfares. Get lost down the numerous side streets and alleys. Explore. Pass the cell-phone kiosks, the sex shops, and pachinko parlors. A grid of ancient-looking movie posters will strategically appear out of the ether: snarling faces framed by guns and knives. Yazuka. Gamblers. Tumbling dice and hanafuda cards.

This is how the Shinjuku Showakan announces itself, in images frozen in time from Japan’s Showa era (1925-1989).

Don’t sneeze at the ¥1300 admission fee. You’ve saved a few, compared to the ¥1800 admission for a first-run flick, and can use it on the vending machine in the lobby. Pay the nice old lady inside the box-office window. She’ll tear your stub in half.

Walk inside. Look around. Try not to sniff around too much. Curious smells might give you a bad first impression. Adjust the eyes. Some two hundred seats make up the main floor, with additional seating located in a spacious balcony. There’s maybe only forty to sixty or so people in there along with you. Most of them are middle-aged men.

The Japanese word for them is oyaji. And in a culture that worships youth and style, they are probably the most unfashionable people in the country. First and foremost, the Showakan is their place. A hardcore contingent, the Showakan Army, lines up every day before the doors open at noon. They come for all kinds of reasons. To get off of the street. To crash on the cheap. Others come because they have no stomach for Hollywood film, televised entertainment consisting of pop stars eating exotic foods, or trendy dramas about everyday life. The Showakan’s films used to represent the mainstream of Japanese pop cinema. Now these old movies are as alternative as it gets. The Showakan is also a clubhouse for the local yakuza. And with movies like Nihon no don (The Don of Japan) and Soshiki boryoku (Organized Violence) constantly playing, how could it not be?

Perhaps because of the Showakan’s rough-hewn clientele, a bad reputation hovers around the place. Mention it to people out of the inner circle and they’ll warn you about the place as if it were a dragon’s lair minus any treasure. Once inside though, the joint turns out to be down home and nearly benign. By promixity alone, simply walking through the door makes you an honorary oyaji or temporary yakuza.

As if to show there is nothing to be anxious about, some patrons are asleep, peacefully oblivious to whatever might be playing on the screen. Others are prone to distraction, endlessly rummaging through plastic bags, muttering to themselves or at the screen (especially when guns or breasts appear). Still others watch intently. They’ve been inside the theater all day. From the glazed looks of them, perhaps all their lives.

The Showakan’s doors first opened in 1932, when the theater specialized in foreign films (meaning American and European fare), then during World War II it was burnt to the ground, like much of the surrounding area, by Allied fire bombings.

The Showakan rose from the ashes in 1951. Once rebuilt, it played what the major Japanese studios offered and what the public wanted to see. Mostly this meant sword films or yakuza films with period flavor. There was one major patriotic stipulation: the films would have to be Japanese. If the Showakan was going to cultivate a loyal audience, then it had to draw the line somewhere.

In the sixties, as the all-pervasive popularity of television began to shut down theaters, and domestic studios sold their property to cash in on the growing value of real estate, the Showakan managed to hang on. You can thank the yakuza for that mostly, even though they sometimes demanded free admission from the hapless staff. During turf wars, fights could break out between rowdy patrons. Toei shot scenes for movies inside. The programming switched to triple bills daily, and time marched on, at least outside the increasingly hermetically sealed Showakan.

Then as now, two genres utterly dominate the programming: yakuza films and horror movies. Sonny Chiba is a big draw here. So is anything directed by Nobuo Nakagawa. Far and away the most popular fare is culled from Kinji Fukasaku’s seventies-era Jingi naki tatakai (Fight without Honor and Humanity) series.

The management is constantly struggling to obtain raw materials, but film prints, some of which have been in circulation for upwards of thirty years, are not always in the best of shape. The same goes for what little advertising materials the studios can be bothered to cough up. When original posters and film stills are not available, illustrator and Showakan schedule-maker Happy Ujihashi goes to work and paints smashing new interpretations all his own. He also creates a monthly Showakan News flyer that’s distributed throughout the neighborhood.

So the place might be a little beat-up in places. (Whoa! Watch out for that bathroom.) There’s still much to be proud of. Sound and projection are first-rate. So is the programming. Living history in light and shadow.

The Showakan management has made recent attempts to turn the oyaji onto new stuff from time to time. In 2000, recent films such as Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Serpent’s Path and Sabu’s Dangan Runner (aka Non-Stop) were screened and well received. But the crowd is picky. Takashi Miike’s Dead or Alive seemed like a sure thing, until the English title confused the patrons. Thinking that Kinji Fukasaku could always be counted on, Battle Royale was booked. But it seemed that the old timers didn’t want to watch a movie about high school kids. Especially one with an English title.

Give it another thirty years or so. The next generation of oyaji will probably need a place deep in Tokyo to call home, too. And the Showakan will be there to mop up when they do.

[author bio="Follow the author and the book here!" image="author-pat2.jpg" facebook="http://facebook.com/Otakuversezero" twitter="http://twitter.com/patrick_macias" website="https://www.amazon.com/TokyoScope-Japanese-Cult-Film-Companion/dp/1569316813"]

PROLOGUE

This is the story of a lost chapter in Japanese film history. It is a missing reel of cutting-room-floor footage that needs to be edited back in before the Big Picture, the dai eiga, nears true completion.

You might already know some of the story.

From the postwar years on, Japan produced some truly amazing films and filmmakers. The works of Akira Kurosawa, Yasujiro Ozu, Kenji Mizoguchi, Kon Ichikawa, and Nagisa Oshima, for starters. Acclaimed. Award winning. Ever present. The Western perception of Japanese cinema has been dominated by them for decades now. And not without good reason.

Yet during the same period, let’s say from 1950-1976, during which the big guns created their signature works, Japan’s popular cinema was also at its peak. During the late fifties and sixties especially, impressive moviemaking machinery was in place: a star system, a studio system, and an audience that supported Japanese films by demanding a host of new double- and triple–features every week.

A new generation of young filmmakers had to be ushered in to grind ‘em out. The rules were simple. Keep it cheap. Do it on time. Above all, make it entertaining.

Although these limitations were non-negotiable, the artists and journeymen who agreed to them were granted an enormous amount of creative freedom. As director Norifumi Suzuki (who helmed the almost unbelievably blasphemous School of the Holy Beast) has said in interviews, the only taboo that could not be transgressed was the Emperor. But aside from that, and a strict no-show stance on hardcore sexual imagery, the B- and C-class filmmakers could get away with anything.

Filmmakers like Norifumi Suzuki and screenwriters like Takeshi Kimura (aka Kaoru Mabuchi) sized up the situation and ran with the ball. They were progressive, free-thinking individuals who had endured the war, the subsequent American occupation, and were now working in a highly competitive and commercial mass medium.

Film studios, forever besieged with labor issues, had long held considerable attachments to the right wing and organized crime. The people who actually directed and wrote these films were frequently far more left of center. Yet these institutions and individuals needed each other. And out of the friction came both conflict and creativity.

Flickers from the late sixties and earlier seventies: yakuza movies, porno flicks, karate killers. This was the era of true Japanese exploitation films, primarily intended to rope in blue-collar types and young men who had migrated to the big city to take part in the economic miracle. The target audience got what it wanted in spades: criminals, monsters, escapism, shivers, sex and violence.

These movies, once considered so disposable by the parent studios that film prints and negatives were frequently destroyed soon after release, were often nothing less than the manifestos of the people who made them. Kinji Fukasaku’s yakuza films spoke as eloquently on the turmoil of postwar Japan as any history professor could. Shunya Ito’s Female Convict Scorpion series was a scathing critique of Japanese imperialism and patriarchy. Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster was a reaction to a horrific series of industrial pollution accidents. You didn’t even have to dig very deep to get the message. These “trash films” proudly wore their subtext on their sleeves.

And they looked great. Although frequently made on the quick and cheap, consummate professionals handled the raw materials all down the line. Japanese aesthetics of composition and design made their genre films truly special. During this quarter-century streak of Japanese film, no one consistently made more handsome pop films, save perhaps for the Italians (God bless them).

But it is not like many outside of Japan knew about any of this when it was happening.

Japanese studios, either out of sheer laziness or by assuming that there was no audience for these films abroad, did amazingly little to promote their titles overseas. And the ones that did make it to foreign screens? They were marketed to children, drive-ins, grindhouse theaters, and other channels of distribution either beneath the contempt, or simply the radar, of both the general public and “Japanese film experts.”

The people who did follow the trail saw enough to form lasting cults around. By the seventies, Japanese monsters and Sonny “The Street Fighter” Chiba could claim loyal acolytes world-wide.

During this same era in Japan, the tide went out for the film industry. Domestically produced movies had lost the lion’s share of their audience to TV shows and Hollywood blockbusters. The postwar generation of filmmakers had lost their playground. They moved to television, retired, or expired. By proxy, Japanese films became cult films in Japan too.

Cut to now.

A new Japanese New Wave is currently piquing the world’s interest. Filmmakers like Takashi Miike (Dead or Alive), Kiyoshi Kurosawa (Cure), Kaizo Hayashi (The Most Terrible Time in My Life), and Hideo Nakata (The Ring) have taken film festivals and international audiences by storm. They seem to have sprung from nowhere. People reach for comparisons, points of origin, and find a black hole.

The truth is that these new superstars of Japanese film sprang from the soil of the previous generation. Hideo Nakata first became a director at Nikkatsu studios during their notorious roman porno heyday. Kaizo Hayashi quotes freely from old yakuza films and ninja movies.

The old timers showed these future directors that there was nothing wrong with making genre films. Even the time-honored dance of time and money could give one immense artistic room to maneuver. And maybe most importantly, all of Japanese film, from A to Z, deserved to be on equal historical footing.

Take Takashi Miike. He began his film career as an assistant director to Shohei Imamura, yet he claims the work of Yukio Noda as a major inspiration.

Shohei Imamura? Sure. The Cannes-winning director of Insect Woman and The Pornographers. But who the heck is Yukio Noda? Answer: turn to page 51 of this book, for a write-up of his Golgo 13 movie starring Sonny Chiba, which can be found on US home video without too much difficulty.

The films obtained for review in this book were found any way we got them. Mostly this meant video. English-dubbed, raw Japanese, PAL/NTSC transfers, crappy Hong Kong VCDs, you name it. Several titles were procured by trading with a Japanese pen pal in exchange for contraband tapes of House Party 2 and 3 (perhaps he’s writing Kid ‘N Play Scope). We even hopped on a plane and went to Japan a couple of times. If we listed a movie as being “available” that means that you can get it on the internet, or bug your local video stores, or gray-market dealers, and probably come up with a copy.

If we wrote up a certain title, that means it gave us some thrills and some laughs and inspired us enough to generate a missive. This is not a book with a ratings system meant to divide things up into “authoritative” piles of Good and Bad. And to be honest, when it comes to these kinds of movies, there isn’t a heck of a lot that we don’t like.

After all, this book is subtitled The Japanese Cult Film Companion. We’re not trying to be an encyclopedia, Psychopathia Sexualis, or the phone book. We just want to take you off the beaten path of Kurosawa, Ozu, and Oshima for a bit and show you where the wild things are. Which means our first stop is Tokyo and the Shinjuku Showakan, the greatest movie theater in the world.

And immediately following the short subject: the main feature, an alternate history of Japanese film, a cult movie, proudly presented...in TokyoScope.

Patrick Macias

Sacramento—San Francisco—Japan, 2001

[author bio="Follow the author and the book here!" image="author-pat2.jpg" facebook="http://facebook.com/Otakuversezero" twitter="http://twitter.com/patrick_macias" website="https://www.amazon.com/TokyoScope-Japanese-Cult-Film-Companion/dp/1569316813"]

TokyoScope - The Japanese Cult Film Companion

Without the support of some very fine folk, TokyoScope almost certainly would have been a scratchy, silent 8mm affair projected on a bedsheet somewhere. Super-sized serving of thanks and appreciation are in order:

Editor and ringside trainer Alvin Lu imparted valuable lesson after valuable lesson and was a great friend every step of the way. Designer Izumi Evers brought immense talent and experience to this project, often doing triple shifts as a translator, coordinator, and benshi narrator. Happy Ujihashi’s constant stream of illustrations delighted, inspired, and supplied the strength to go on. Viva la Showakan! Praise be also to Tomohiro Machiyama, trusted friend and founding editor of Eiga Hi-Ho magazine, who selflessly provided information and analysis, supplied films, and helped open doors on countless occasions. And major indebtedness to TokyoScope’s crack team of translators, who include Andy Nakatani (who gave his time often, freely, and always in good humor), Akemi Wegmuller, Yuji Oniki, and Zachary Braverman.

Lots of other people, contributors, friends, folks who helped one way or another: Kinji Fukasaku, Takashi Miike, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Risaku Kiridoshi, TDC Fujiki, J-Taro Sugisaki, Mahiro Maeda, Kiichiro Yanashita, Aki Kameda, Toshiko Adilman, Taro Goto, Anne McKnight, Jason Thompson, Carl Horn, Chuck Stephens, David Weisman, Robert Houston, Jim and Gibran Evans, Mark Walkow, Trish Ledoux, Laura Heins, Roy Wood, August Ragone, Femke Wolting and the Rotterdam International Film Festival, Chris D. and the American Cinematheque, Mona Nagai and the Pacific Film Archive, my father, the makers of Deva Absenta, and everyone at Tidepoint Pictures and Viz Communications.

And a final outpouring of deep gratitude in the general direction of Hyoe Narita, Seiji Horibuchi, and especially Satoru Fuji for the desk, the computer, and the chance to write a book about crazy Japanese movies.

P.M.

[author bio="Follow the author and the book here!" image="author-pat2.jpg" facebook="http://facebook.com/Otakuversezero" twitter="http://twitter.com/patrick_macias" website="https://www.amazon.com/TokyoScope-Japanese-Cult-Film-Companion/dp/1569316813"]