Art attempts to create the impossible with limited means. Sometimes this gives birth to works of greatness. Sometimes it leads to giant monsters.

Is the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel the actual Glory of the Almighty made manifest? No, it is more like a really good celebrity impersonation.

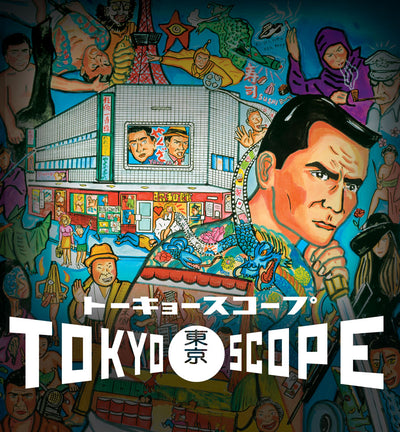

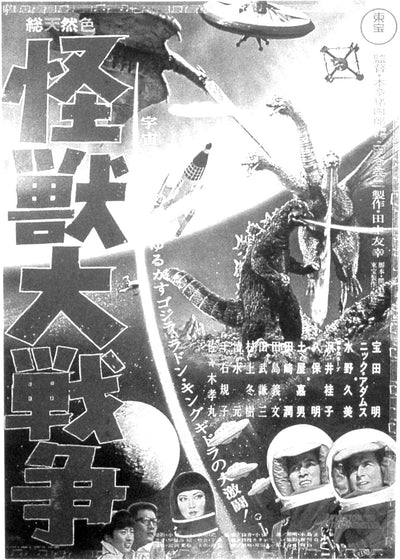

And whatever you feel about movies such as Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster or War of the Gargantuas, Japanese monsters are part of this noble tradition.

In addition to wielding paint and brushes, the filmmakers and technicians behind Godzilla, Gamera, and their kith and kin must keep a very big palette at their disposal, one with rubber monster costumes, optical printers, miniature cities, and computers in order to create an illusion of reality.

“Film is a synthetic art form in every respect,” said the late Ishiro Honda, director of 1954’s Gojira (Godzilla) and one of the founding fathers of the tokusatsu, or special-effects film. “It is also a form of synthetic techniques. The filmmaker is an artist, but at the same time he must also be a scientific technician.”

Michelangelo, himself a multitasking sculptor, architect, painter, and poet, would have made great monster movies.

After studying 1933’s King Kong and 1953’s The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, and using special-effects skills gleaned from numerous domestically produced World War II propaganda films (such as 1942’s The War at Sea: From Hawaii to Malay), it was the Japanese who erected the dynasty of the kaiju eiga—the giant monster movie.

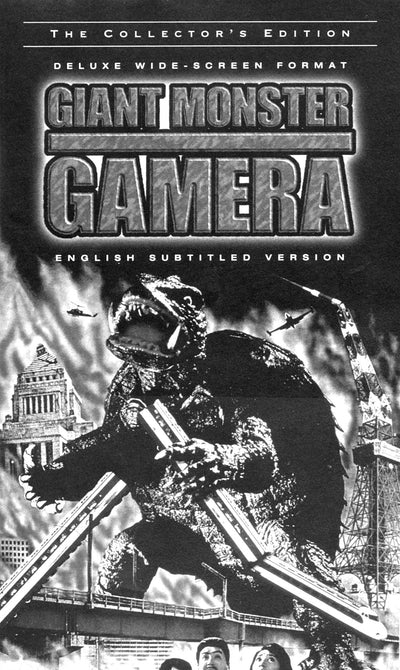

Even if you’ve never heard of Gappa the Triphibian Monster or Gamera the Invincible, everyone knows Godzilla. From Thailand to Germany (even though, okay, he’s been sold there on occasion under the name of “Frankenstein”), and all points in between, no other Japanese films are as widely seen or available. The Lizard King receives more recognition, and garners a bigger audience, than Akira Kurosawa.

Gomer Pyle was a Godzilla fan. But so is Martin Scorsese, who once asked to meet Ishiro Honda on the basis of the fondly remembered films he saw as a kid in a Brooklyn theater.

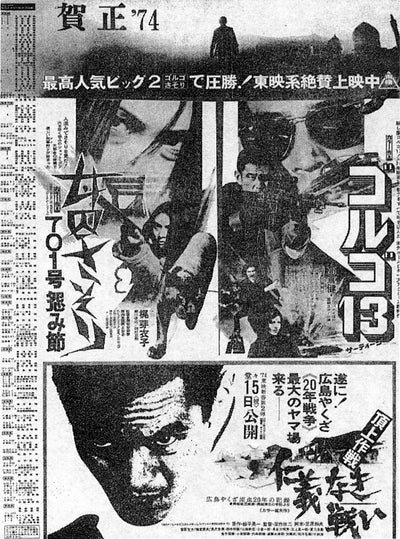

Kaiju eiga are the films of one’s childhood, screened at matinees and on Saturday morning TV. In Japan, entire tokusatsu films were cobbled together and edited down just to show at kiddie film festivals. Why not? Stepping on a city and spewing atomic heat death is the ultimate temper tantrum. To criticize these films as childish is redundant.

At the other extreme, some people take kaiju films as seriously as sacred texts. Academics concoct overreaching theories about them regarding the state apparatus of postwar Japan. Hollywood pisses away millions on a stale American Godzilla movie. Humorless fans threaten to kill each other over which Godzilla suit was best designed.

In truth, there was only one great explosion. All else has been aftermath, an illusion of life in the bomb shelter.

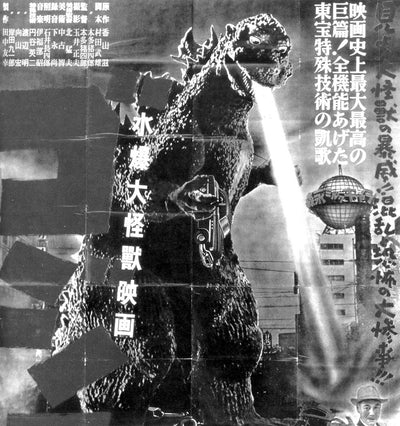

Toho Studios’ original Gojira (1954) was an anxiety-ridden film explicitly about the H-bomb, an unprecedented mix of monstrous fantasy and documentary reality, the juxtaposition of ticking Geiger counter and dazed child its single most disturbing image.

Follow-ups would handle the primal theme either too lightly (King Kong vs. Godzilla), too heavy-handedly (Godzilla 1985), or not at all. References to reality gave way to a flood of fantasy. But every now and then, synchronicity steps in and reminds us where it all began.

In Godzilla 2000 (actually a pretty poor excuse for a Godzilla film), the monster attacks a nuclear power plant in Tokai. It is exactly the same location where a critical nuclear fuel plant accident occurred on September 30, 1999. Heavy handed allegory? But the script to Godzilla 2000 was already well completed before the accident.

If the genre has long since reached its dead end and chosen to endlessly reenact the same rituals (the winking self-awareness of Gamera III admits as much), kaiju eiga will forever function as Trojan horse—as point of entry into the less traveled woods of Japanese film and worlds beyond. Those hooked on Godzilla at an early age may, by adulthood, know that Toho producer Tomoyuki Tanaka was not only behind numerous Godzilla films, but also Kurosawa’s The Bad Sleep Well.

Giant monster movies and the sublime are not as far apart as they seem. Kurosawa may have gotten the accolades, but the monsters got something more. A mythology, a religion, even.

In Godzilla we trust.